- Yaara Keydar

- Oct 9, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 14, 2025

Blue is one of the most beloved colors worldwide, yet its widespread popularity is a relatively modern phenomenon in human history. Despite being one of the primary colors, blue is surprisingly rare in nature. Few minerals, animals, or plants can produce it directly, making its history mysterious and captivating.

Across thousands of years, blue has held deep, multifaceted meanings in various cultures intertwined with religion, language, gender, and emotion. However, due to its scarcity, the production of blue in Europe took two main routes: one for art and the other for fabric dyeing.

Ancient Blue: From Pharaohs to Royalty

The history of blue reveals a story of ever-changing perceptions. The ancient Greeks and Romans didn’t even have a word for blue. To Homer, the sea was “wine-dark,” and the color was absent from descriptions of the rainbow. Blue was often associated with the Celts, who supposedly painted their bodies blue for battle, while blue-eyed women were considered of loose morals.

Yet, blue did exist. It was used in dyeing fabrics, as seen in decorative murals from Pompeii. The ancient Egyptians, with their love for lapis lazuli and turquoise gemstones, created the first synthetic blue pigment to mimic the hue of these rare stones. Known as "Egyptian blue," it was made from silica, lime, copper, and alkali and adorned various objects in everyday Egyptian life.

Royal Blue

In early modern Europe, blue textiles were dyed using woad, a Mediterranean plant. By the Middle Ages, woad cultivation in England, France, and Germany brought immense wealth to various regions. However, blue became a symbol of nobility due to its costly and unstable nature. The working class wore browns and greens, while the elite wore blue.

Blue wasn’t just expensive for clothing—it was an incredibly pricey pigment for painters. Due to its high cost, it was reserved for the most sacred subjects. During the Renaissance, no figure was more important than the Virgin Mary, who was almost always depicted wearing blue, turning the color into a symbol of purity, humility, and divinity.

Artists ground the semi-precious lapis lazuli stone into ultramarine, a deep blue pigment famous for adorning Renaissance paintings. The name, from Latin ultramarinus, meaning "beyond the sea," referred to the origins of the stone, imported from mines in Afghanistan. Ultramarine was so costly that some paintings were left unfinished due to the prohibitive cost of the pigment. Even Michelangelo couldn't afford it, while Raphael only used it for top layers of clothing. In contrast, Titian became renowned for his lavish use of ultramarine, as seen in his painting Bacchus and Ariadne, which has an expansive blue sky.

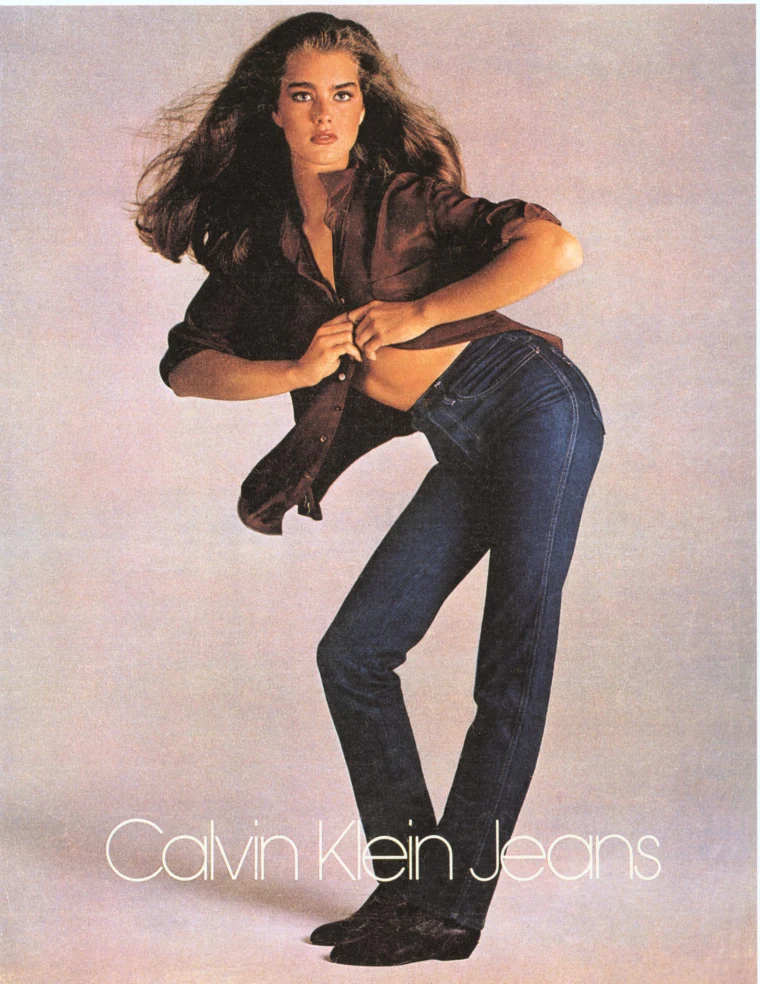

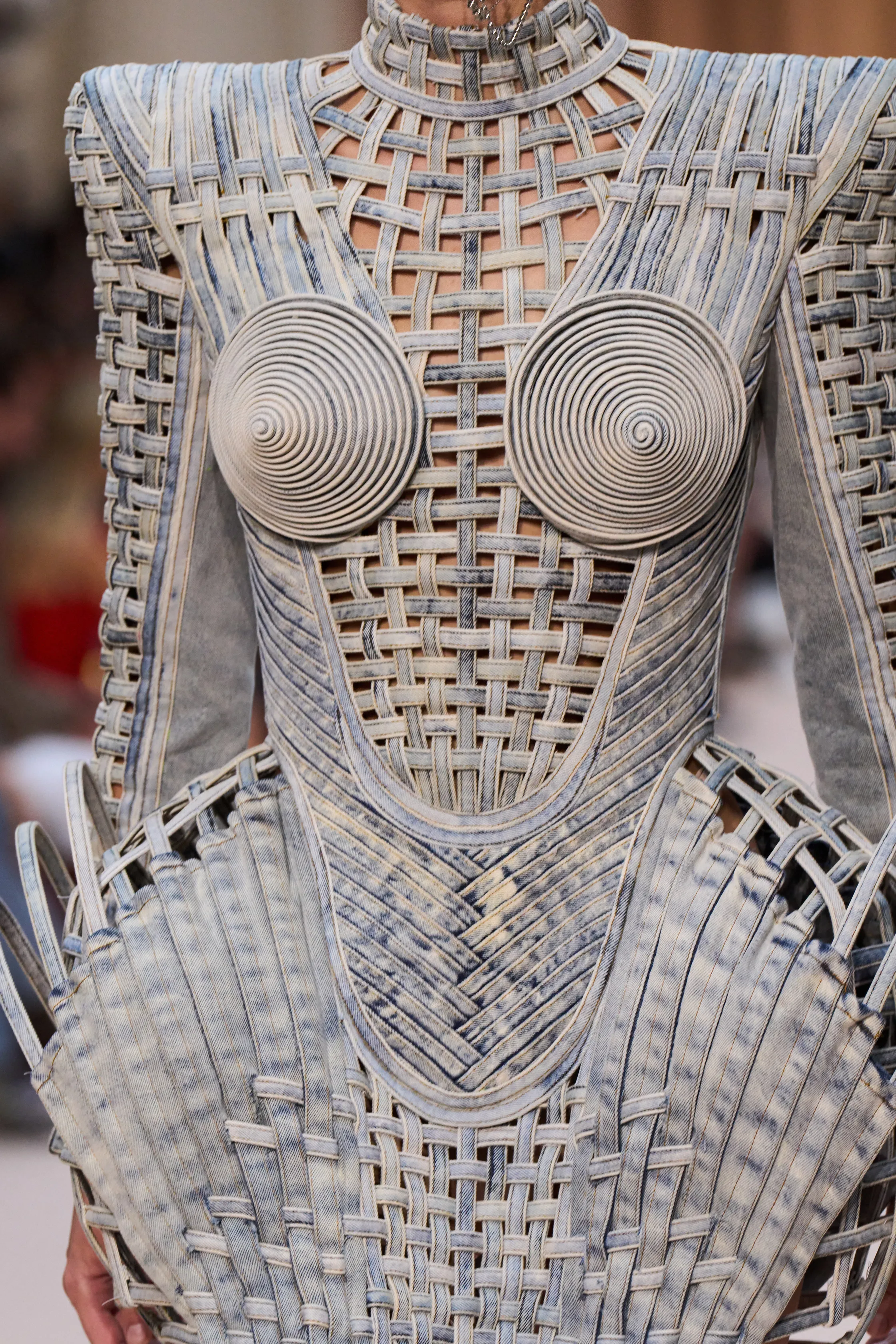

Indigo: From Workwear to Fashion Icon

How did denim, once humble workwear, become a fashion staple? And why is it almost always blue?

Though blue was costly in art and porcelain, it became cheaper in textile dyeing. Over time, blue fabric grew so common in Europe that men and women of all classes wore it. However, a new blue dye called indigo shook the European textile trade in the 16th century.

Indigo, a resilient pigment, became widely used for dyeing textiles and printing. Historically, its complex production made it highly sought after, sometimes valued as much as gold—hence the nickname "blue gold." Derived from various natural sources, the most important for our story is Indigofera, a plant that became the foundation of a global industry, dramatically impacting social history and even the institution of slavery.

The plant originates in tropical regions, most notably in India, which gave indigo its name (from Indicum, Latin for India). Indigo dyeing has ancient roots, with textiles dyed in indigo found in Peru from 6,000 years ago. The tomb of Tutankhamun contained indigo-dyed fabrics, and it was commonly found in sarcophagi across Egypt. Indigo even made its way to Japan after the 10th century, where it would rise again in prominence in the 20th century.

Producing indigo was an arduous process. After harvesting, the plant was soaked in large vats of water for 24 hours, allowing the leaves to ferment. As the water oxidized, it turned blue, and after another day, the indigo settled at the bottom. This paste, after filtration, was then formed into bricks for trade. While the process may sound picturesque, it reeked terribly, often compared to the stench of rotting flesh. Once the indigo paste was ready, it was crafted into valuable trading goods.

Historically, indigo dyers were often Jewish, especially in Asia and North Africa. Dyeing was considered a lowly profession due to its staining and foul odors. Still, by the Middle Ages, Jewish dyers mastered these ancient techniques, building strong trade relations and transforming from laborers into prosperous merchants. Indigo traveled with Jewish traders from India to Egypt, Egypt to Tunisia, and Tunisia to Italy and Spain—the gateway to the West.

Demand for indigo soared, driving significant economic growth in India and America. By the early 18th century, indigo profits in America surpassed those of sugar and cotton. During the American Revolution in the mid-18th century, the dollar was so weak that indigo bricks were used as currency in place of money.

how did blue become the color for boys and a symbol of the working class?

Until the 16th century, the blue dye used for European fabrics was extracted from a biennial plant called woad. Extracting the dye from the plant's leaves was laborious, yielding a substance known in French as pastel. As I mentioned earlier, it wasn’t very stable, often fading quickly. But by the end of the 16th century, blue’s status changed again, this time due to religious upheavals and technological breakthroughs in the production of blue fabric dyes.

In 1517, the Saxon preacher Martin Luther promoted the Protestant Reformation across northern Europe. One outcome of this dramatic cultural and religious shift was a change in masculinity and fashion. But what does this have to do with blue?

Protestant ideology believed that one’s fate was predestined and that hard work during life could elevate one's status before death—where wealth signified a path to heaven and poverty, a descent to hell. This belief led to a new economic outlook that later fed into capitalist ideals.

Men were now expected to be productive individuals, investing their resources in education, labor, and business. This shift also altered how masculinity was represented, simplifying men’s fashion and drastically reducing the use of color. The Protestant palette revolved mainly around white and dark shades, including blue.

Around this time, indigo reached Europe. It was more concentrated, producing a richer, more durable blue. Despite attempts by the governments of France, Germany, and Britain to block its import in the 16th and 17th centuries, indigo managed to penetrate European markets.

Efforts to simplify men’s fashion were met with fierce resistance in France. King Louis XIV saw fashion as an economic lever for France, and during his reign, the country experienced a commercial and cultural revolution that positioned it as Europe’s dominant power. This also included flourishing textile and fashion industries. French men’s fashion remained colorful and ornate despite the rise of Protestantism.

However, Catholic nations in southern Europe, such as Russia, Italy, and Spain, slowly began adopting French styles. By the early 18th century, most of Europe embraced more straightforward male attire. This trend continued into the 19th century when men’s fashion became increasingly uniform.

At the same time, new gender norms emerged. Women retained colorful freedom in their clothing, while men donned darker, more uniform outfits.

The discovery of Prussian blue in 1704 by painter and pigment-maker Johann Jacob Diesbach changed the game. Soon after, a vast industry for dyeing fabrics in Prussian blue arose, operating alongside the indigo trade. By the 18th century, blue had become a staple in men’s wardrobes.

Blue's meteoric rise in men’s fashion continued into the 19th century, thanks to technological advances that allowed the synthetic production of blue dyes. As it became easier to produce, blue also gained prominence in government institutions across Europe, becoming the color of military, police, and railway uniforms. Thus, dark shades of blue became symbols of authority and masculinity. Its durability and affordability made it a favorite among workers and manual laborers, giving birth to the term “blue-collar workers,” representing the working class. At the same time, professionals came to be known as “white-collar workers.”

Indigo and Jeans

Contrary to popular belief, Levi Strauss didn’t invent jeans, but he did invent the version we recognize today, laying the groundwork for much of what we know about branding, marketing, and product development.

Levi Strauss, a Jewish immigrant from Bavaria, arrived in America in the early 19th century. During the Gold Rush, he moved to San Francisco, hoping to expand his family’s dry goods business (selling essentials like sugar and tobacco). He quickly noticed the frustration of workers, particularly coal miners, loggers, and ranchers. Their physically demanding work often caused their trousers to disintegrate within days. At first, Strauss began sewing trousers out of denim, which he sold wholesale.

But why denim? And what exactly is denim? Denim, or jeans fabric, is woven in a diagonal weave known as twill, usually made from cotton fibers. This weaving style makes the fabric incredibly strong, and its durability made denim the perfect choice for work clothes, especially for laborers and miners who needed to bend and work on their knees.

Legend has it that denim was named after the French city of Nîmes, but today, researchers argue it likely originated in England in the 16th century. The name “denim” was likely given a “French” twist to sound more appealing to merchants. Similarly, the name “jeans” probably came from the French word for the Italian city of Genoa, which produced a similar fabric.

And what’s the connection to indigo?

Natural indigo was solid and quickly penetrated the fabric’s fibers, making it the dye of choice for jeans. Because jeans were workwear, the indigo dye increased their value, and people knew the fabric would last longer.

Back to Levi Strauss: After selling wholesale jeans for a while, Strauss received a letter that would change the course of his life. It was written by Jacob Davis, a Jewish immigrant and skilled tailor who had lost all his money in a failed coal investment.

While working as a tailor, Davis discovered that jeans often tore, particularly around the pockets. He devised a brilliant invention: strengthening the seams with copper rivets to better attach the pockets. After producing a few pairs and receiving enthusiastic feedback from customers, Davis realized the enormous potential of his idea—but he didn’t have the funds to file a patent. So, he wrote to Levi Strauss, proposing a partnership. The rest, as they say, is history.

In 1873, they introduced the first jeans with metal rivets and the famous double yellow stitching, designed to reinforce the seams and highlight the product’s quality. Levi’s riveted jeans enabled the branding of jeans as a durable product and the company patented metal rivets. For nearly 20 years, Levi’s was the only company allowed to use metal rivets in clothing, securing its position as a market leader. What’s remarkable is that the cut has hardly changed if we look at jeans from that era.

By the end of the 19th century, a German scientist created a synthetic alternative to natural indigo—an easy-to-produce, fast, and cheap dye. Sales of natural indigo plummeted, while mass production of synthetic indigo grew to unprecedented levels, making blue jeans more popular and accessible than ever.

Blue and Gender

Blue treads a fine line between gender and social perceptions. Today, blue is associated with boys and masculinity, just as pink symbolizes girls and femininity. But has it always been this way? History tells a much more complex story, where blue was once a shared color for both genders.

Over time, the development of blue in the textile industry sparked a revolution in the meaning of blue clothing. It symbolized masculinity and the preferred choice in men’s fashion. Yet, this is just a twist in a much longer story.

What seems like a natural division today—pink for girls, blue for boys—is a relatively new phenomenon. History tells a different tale. Until World War I, boys and girls in Europe dressed alike. Boys wore dresses, girls wore blue—and the world didn’t fall apart.

A fascinating example can be found in Renoir’s 1878 painting Madame Charpentier and Her Children. In the painting, we see the mother seated with her children—and I say “children” deliberately, as one of the children dressed in a gown is, in fact, a boy.

In the 19th century, the perceptions were the opposite of what we know today. Blue was considered delicate and feminine, associated with the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. On the other hand, pink was seen as strong and assertive, more fitting for boys.

Thus, blue invites us to reflect on its natural beauty, how we ascribe meanings to colors, and how societal perceptions change over time. It reminds us that what seems natural and obvious today results from complex, ever-evolving cultural processes. With its rich and varied history, blue continues to challenge our perceptions and invite us to rethink gender, color, and everything in between.